Battles of Brandywine

Battle of Germantown

Africans at the Battle of Germantown

By Noah Lewis and Joseph Becton

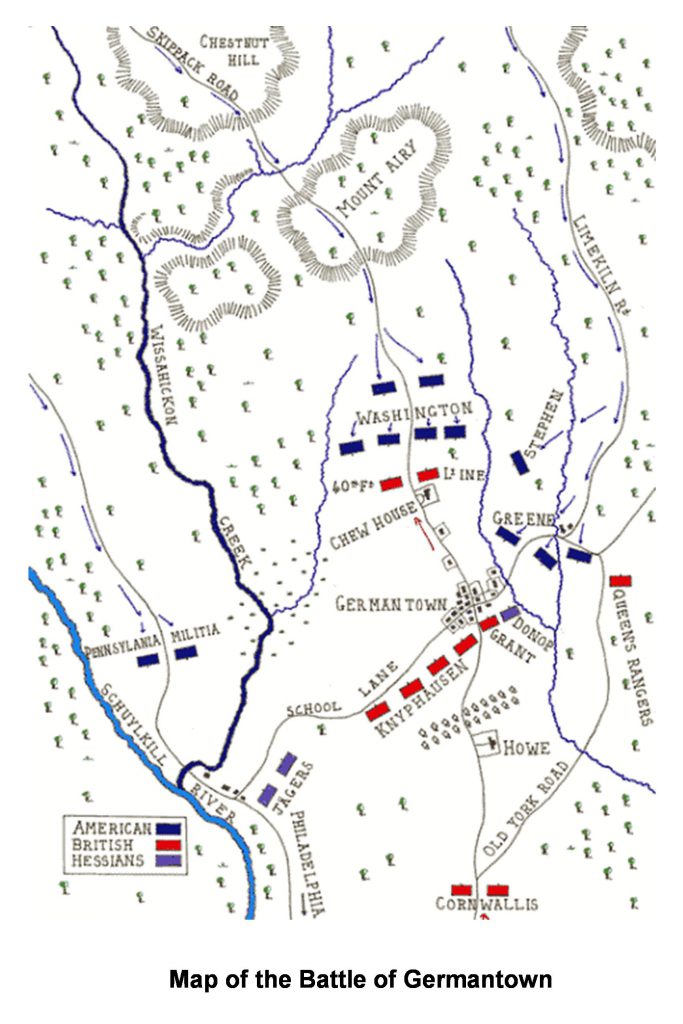

As you watch the Battle of Germantown, you might think back to how it must have been. Think not only about the leaders and weapons, but also the everyday people. People perhaps much like you. It was a diverse force, a conglomeration of many kinds of people. The man, in whose house the fighting is taking place, is the well to do Judge Benjamin Chew. Today you see armies comprised of German, Irish, Polish, Scottish, English, French, as well as many others. Among these forces are people of African origins.

This war was not to end slavery, independence did not mean freedom and yet enslaved Africans still volunteered along with their free counterpart.

What the army offered was:

- Money $6 2/3 Dollars a month

- Cash Bounty on enlistment

- Food

- A new suit of Clothes

- Social status

- Travel

- Land Bounty at the end of the war

Although these Africans had the strong desire for freedom, what nurtured that desire, varied. Africans could serve the American army in at least four ways. (1) As a freeman. Like Ned Hector, of the Proctor’s 3rd Pennsylvania Artillery. (2) As a Runaway. Escaped slaves like Peter Williams of New Jersey escaped from his loyalist owner. Job Lott of the 5th North Carolina Regiment “came over from the British with a wagon of Flour”. Enslaved (held as a slave) William Lee, George Washington’s Valet, went everywhere with The General. Jack Arabus of the 7th Connecticut sued for his freedom after the war. (3) As a substitute, a replacement to serve in place of someone. They could be a free or enslaved person, hired or brought. Lott Ford served as substitute in Hall’s 1st Delaware. Joshua Payne of the 14th Virginia was another example. Often the master or his son, would promise freedom for service. Often the promise was not honored. Such was the fate of Gad Asher of the 2nd Connecticut and Samuel Sutphin of the New Jersey Militia. The State or Central Government could buy an enslaved person to serve in the Continental Line. The Rhode Island Slave Soldier of Act 1778 as an example. The Continental Congress offer $400 dollars as compensation to the owners for each volunteer. (4) You could have also come from outside this country. Later in the war the Spanish joined the war and African soldiers from around the empire fought under General Galvez in Florida. Africans in the French forces fought in the Battle of Savannah, Georgia the country they came from is now Haiti. They all shared the same hope, but had different reasons.

The Africans were divided; they served on both sides, but were united by the same desire to be free and remain free. They wanted to have some control over their lives. Three to five thousand “People of Color” served the American cause; seven to ten thousand served the British. General Washington would command the most integrated army up until 1948 when Harry S. Truman would re- integrate the army for the Korean conflict. . General Washington would also command at least three majority African regiments: one from Marblehead, Massachusetts, Glover’ Marblehead Marines, one from Rhode Island, Lt Colonel Christopher Greens 1st Rhode Island regiment and the Volunteer Chasseurs from Haiti that battled at Savannah, Georgia and Charleston, South Carolina. These units would play an important part in America’s struggle for independence. In New York, the Marbleheaders would save the American Army from annihilation when the army would find themselves trapped against the river at Brooklyn Heights, New York. Under the cover of night and fog, under the noses of the British warships, men would quietly row their boats to the entrapped Americans and shuttle them to safety. Some would make that trip as many as eleven times. What many don’t realize is that many of those men rowing those boats were Black sailors from Marblehead, Massachusetts. That night those men saved the American army and allowed us to continue our fight for independence. It could have been all over, finished if not for the actions of these brave men. There would be Blacks that would serve as spies for the American cause. One of which was James Armistead Lafayette. He added the last name to honor the one he was spying for. Having learned information about British going to Yorktown, he proceeded to get that information to Washington. Acting upon the information he received, General Washington would lay siege to the British at Yorktown. The Americans ran into problems when they could not bring their large cannons close enough to make effective use of them. This was due to the defensive fortifications, readouts, the British had erected. The decision was made that two of the readouts would have to be taken. The Rhode Island regiment was sent in with guns unloaded, bayonets fixed, to take out one of the positions and the French was assigned the other. They accomplished their objectives and the cannon were brought up and effectively used, leading to the surrender of the British. By the end of the war ten to twenty five percent of General Washington’s army would be people of color. The term “person of color” referred to anyone whom was not considered white, so that included the Native Americans as well. What do you imagine would have happened if General Washington would have had a quarter of his army missing? The truth of the matter it took all of the diverse Americans coming together to win our independence.

Africans at the Battle of Germantown

Edward “Ned “ Hector – Bombardier/ Teamster for Proctor’s 3rd Pa Artillery. There is a painting of four cannons bombarding the Chew House. That unit is Proctor’s 3rd Pa Artillery and it gives you the point of view that Ned Hector would have had during that battle. As a bombardier he is manning one of the three rear positions of the cannon. As a teamster he is hauling the gunpowder and ammunition and most likely pulling a cannon behind his wagon. In the previous Battle of Brandywine he ignored his order to abandon his wagon, horses, and cannon to retreat. Instead, at great risk, chose to save his wagon, supplies, and horses. Sixteen years after his death in 1834, Conshohocken named a street after him. [see painting and Noah with history sign]

Oliver Cromwell a Mulatto from New Jersey. He served In July 1777 under Captain’s James Lowery.

Nathaniel Bowman and Elisa Shreve, Second Regiment NJ. He served at Valley Forge and the Battles of Germantown October 1777, Monmouth June 1778. He was discharged in June of 1783. He got a Land bounty of 100 acres.

Sgt. Issac Brown, a Free Farmer born 1760. He was literate and served in Colonel Campbell 5th, 11th, and 15th Virginia Regiments at Brandywine and Valley Forge.

Joshua Payne from Carson City Virginia, enlisted as a substitute in Westmoreland County in Colonel Charles Lewis 14th Virginia regiment.

William Clark, a “free mulatto” from Culpeper County, Virginia, for his service in Lt. Colonel John Jameson Dragoons and 2nd Continental Dragoons regiment 1777-1778 received two 100-acre bounty land warrants.

Daniel Williams, a free “man of colour” from Accomack, Virginia served in the 7th, 11th, and 15th Virginia Continental Army as a wagoner. He was drafted into the army and served 4 to 5 years. After the war he move to Pennsylvania and received two land bounty warrants, one for 100-acres, the other for 200-acres.

Caleb Overton, a “free man of colour” from North Carolina served for three years in Abram Sheppard 10th North Carolina Regiments He enlisted July 13, 1777 in Captain Robert Melbain, in August 1778 he served with the 1st North Carolina. He received a 274-acre bounty land warrant. Samuel Overton is his brother served also.

Jack Arabus/Arabas enslaved from New Haven Connecticut Joined Colonel Herman Swift’s 7th Connecticut regiment from 1777-1783, Sued for his freedom after the war.

Drummer Achmet Hamet of Middletown Joined Colonel John Meigs additional Continental Regiment. He was wounded at Germantown, PA. He was born about 1750. He received a pension in 1818 and died 1842. He served at Stonybrook, NY and Yorktown, VA.

So why should Cliveden, the sight of this battle, see fit to include this article highlighting the African contribution to this country’s liberty? Firstly, to right a wrong inflicted on those who were co-participants in this country’s struggle for liberty. Up until recently their contributions were forgotten, along with others such as women, natives, Spanish, and more. Secondly, to instill a national pride in us as Americans. It took all of us coming together to win our liberty. Thirdly, to remind us that African-American history is part of American history. We all need to own it and be grateful for each other. We as Americans, hope to take pride in what we accomplished together and learn from our mistakes and become better for it.