David Library 2012

In Search of Black Among the White

Last summer I had the opportunity to experience a perspective that I was previously the subject of. I remember hearing about this David Library from various sources. As I talked to numerous historical authors invariably they would tell me how they found this bit of information or that bit of information at the David Library. Then they would ask me if I had been able to visit the David Library yet. I was asked this same question from not only authors, but from fellow reenactors as well. They would proceed to tell me what they discovered about their unit or person. These too would end in the question,” Have you had a chance to visit the David Library yet?” Finally, after feeling like I had been left out of something that everyone already knew, (nudge nudge, wink wink) I decided to visit this David Library I had heard so much about. Of course the fact that I had exhausted most of my resources fed an ever encroaching sense of desperation, which helped play a role in my paying a visit to the library as well.

What would this David Library have about black patriots? Not much, like most of them, I could imagine. I must confess, I was surprised that the by the volume and the range of resource materials they had. But what impressed me the most was how willing they were to go out of their way to help me. I had a sense that they believed they were like NASA’s mission control in which they sent out their patrons to explore the vast unknown of history.

And explore I did! I found a lot of useful information about my subject, Edward Hector, a black Revolutionary war soldier who fought in the Battle of Brandywine and Germantown for Col. Proctor’s Third Pennsylvania Artillery. This included information on Ned’s officers, Col. Proctor, who had his horse shot from underneath him as well as the requisition for another horse, and Capt. Hercules Courtenay, who was court martialed for leaving the field of battle,” in an unofficer like way”; Ned’s unit’s history, Proctor’s Third Pennsylvania Artillery which I discovered later became the Fourth Continental Artillery; muster, supply, and pension records for that unit; books researching the battles Ned was in and primary source material about those battles; Gen. Washington’s orders pertaining to his black soldiers, including Washington’s orders not to allow blacks to be enlisted; to name a few.

I mentioned how helpful the staff was to me. There were several times when the staff found information that was useful in my research. They found documents listing Teamster Edward Hector transporting ”pig metal” for Col. Potts in 1780. They also uncovered a document listing a “Negro Hector” owning a wagon and four horses.

In summary, when all this information is combined with other research, the picture of the African-American Continental soldier can be seen in several basic facts. About 3000 to 5000 people of color would fight for the American cause about 7000 to 10,000 would fight for the British. General George Washington would command the most integrated army until 1948 when Harry S. Truman would reintegrate the Army for Korea. Additionally, General Washington would have at least three majority black regiments under his command, from Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island. The black sailors from Marblehead Massachusetts would help save Washington’s army from annihilation when he was trapped at Brooklyn Heights in New York. The Marbleheaders would also help transport Washington’s army across the Delaware River to attack a garrison of Hessians in Trenton. The Rhode Island Regiment would help to punch a hole in the defenses at Yorktown, which would make this victory possible. By the end of the war 10 to 25% of Washington’s army would be people of color. Often, we tend to separate African-American history from American history, but the truth is African-American history is American history! This history belongs to everyone who calls themselves Americans. For without their contribution, as well as many others, we would not be free today.

Last year I found myself talking with a fellow African-American researcher who was writing about the First Rhode Island Regiment. Before the conversation was over, I had suggested to him that he might want to go to the David Library and examine the General Greene papers. Again, at the end of 2011, I was discussing Black American Colonial research with one of the main genealogist for the Daughters of the American Revolution and author of “Forgotten Patriots of the American Revolution“, when the David Library was brought up. She had heard of the David Library and confessed that she wanted to see what resources they had. However, living and working in Washington, DC, she had not been given the chance to do so. She expressed a wish to visit, plans were made, and a day was spent in the library. The day ended successfully, as we left feeling pleased with the research we found. Upon her departure, plans for a return visit was made. On reflection, I thought of how I had been the object of the referral and now I was the referrer. Isn’t it funny how life works?

Noah Lewis

Past Masters in Early Domestic Arts

Past Masters News Vol. 13 Issue 3 Summer 2011

Washington’s Crossing Program Book

ALHFAM 2011

NED HECTOR – REVOLUTIONARY WAR HERO

Noah Lewis

When considering people of the past, it is a good idea to particularize rather than generalize, to say ‘he/she did . . .” rather than “they did . . .” It is often easier to use groups or categories, but too often there are exceptions and misconceptions that occur.

In the case of African Americans in the “world of William Penn,” generalizations are especially difficult. It isn’t just a matter of skin color. There were men, women, and children — an age factor as well as one of gender. There was condition – enslaved, indentured, runaway, and free. There was origin – just off the ship from the Caribbean, just off the ship from Africa, just up from Virginia or Maryland, born in Philadelphia (perhaps a second or third-generation resident). There were artisans, tradesmen, journeymen, apprentices, the unemployed, the idle, beggars, conmen, and criminals. It would be unrealistic to attempt to talk about African-Americans as a group so one person has been selected.

Life for an African man was better in the 18th century than it would be for his descendants in the Victorian period. A free man had legal rights under the law. An African could achieve financial success as in the case of James Forten who became one of the richest men in Philadelphia after the Revolutionary War.[i] Another, Richard Allen, was a teamster and the founder of an African Church movement.[ii] However being an African had concerns. In the 1787 Constitution, there was a clause that allowed a runaway servant to be captured and returned, without the right to plead his case.[iii] An African could be accused of being a runaway and then taken unless someone, more likely a white person, would vouch for him.

In this article, the life of one African-American will be considered.

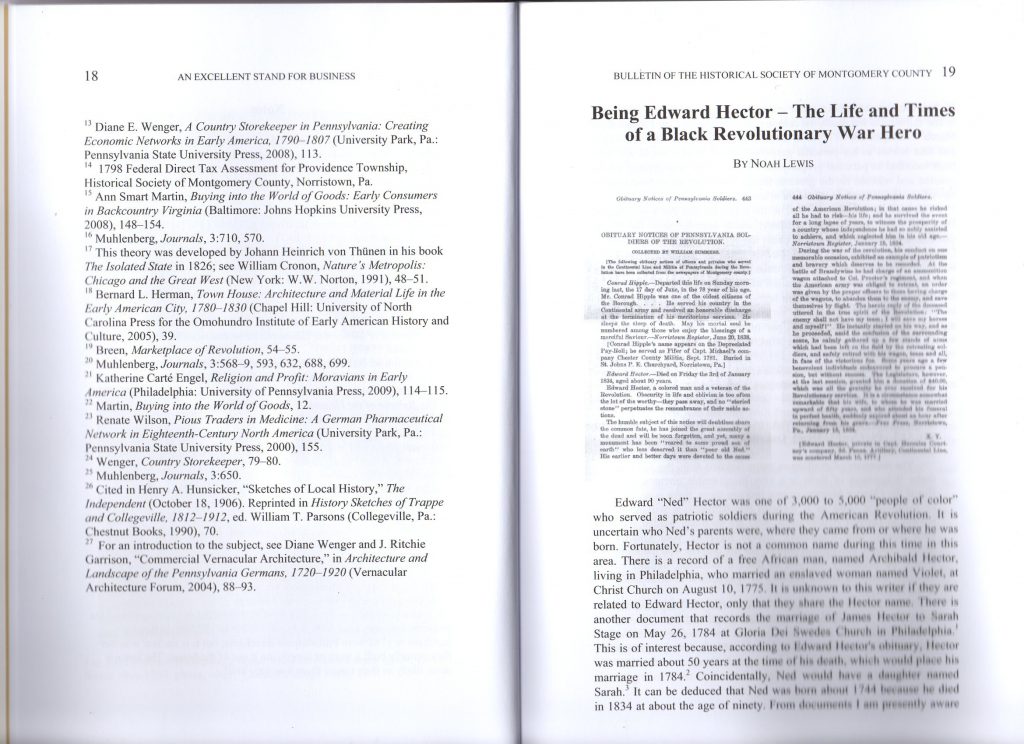

Edward Hector – Died on Friday, the 3rd of January, 1834, age about 90 years.

Edward Hector, a colored man and a veteran of the Revolution. Obscurity in life and oblivion is too often the lot of the worthy – they pass away, and no “storied stone” perpetuates the remembrance of their noble actions.

…………………………………………………………………….

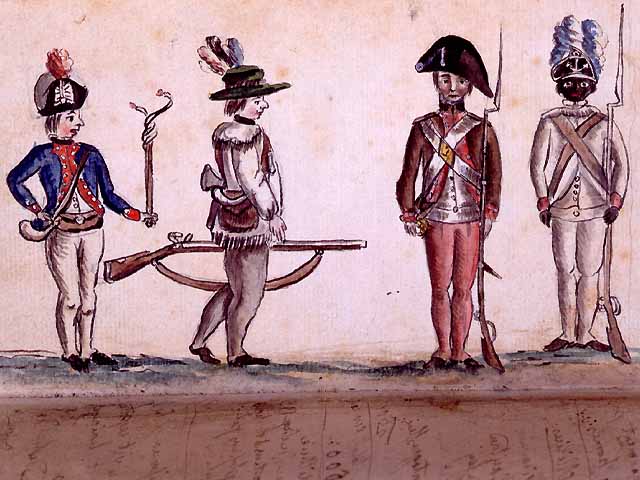

[Edward Hector, private in Capt. Hercules Courtney’s company, 3rd Penna. Artillery, Continental Line, was mustered March 10, 1777.][iv]

The pay of a person of color, like Ned, does not appear to have been different, but was commensurate with his white counterparts. He was part of the most integrated army until 1948 when President Harry Truman re-integrated the army for the conflict in Korea in 1948.

Ned Hector was a teamster. Because of his skill with wagons and horses, he would have made a good living. Much like a craftsman, he could be considered part of the middling sort. There is a good chance that, as a teamster, he would have a degree of skills in reading, writing, and ciphering (arithmetic) so he could do his job and make business transactions. As a teamster with the army, Ned’s function was critical: no gunpowder, no cannons. Teamsters were held responsible for their freight. If they should lose it, they would have to pay for it.[v]

It is uncertain who Ned’s parents were, where they came from or where he was born. Fortunately, Hector is not a common name during this time in this area. There was a free African man living in Philadelphia who married an enslaved woman at Christ Church in Philadelphia.[vi] It is unknown to this writer if they were related to Ned, only that they share the Hector name. It can be deduced that Ned was born in 1743 or 1744 because he died in 1834 at the age of ninety.[vii] From documents about Ned, he seems always to have been a free man.

The earliest mention found of Ned is on a muster roll for Col. Thomas Proctor’s third Pennsylvania Artillery, under the command of Captain Hercules Courtenay on March 10, 1777.[viii] He was listed as a “bombardier.”[ix] Many modern people think Africans were only manual laborers, the listing and the fact that he applied for a pension confirms he was a soldier.[x]

The artillery was considered a special elite fighting force. It utilized the most up-to-date technology of the time, the cannon.[xi] To have an effective artillery team, it was essential for everyone to work well together. Ned was in a very trusted position. If he should fail to do his job or lose his wagon, the artillery he served might be rendered useless.

Ned was reported as fighting in two battles – the Battle of Brandywine and the Battle of Germantown.[xii] It was at the former that a thirty-three year old Ned was remembered for his heroism. We are fortunate to have a first-hand account of this battle from the area where Proctor’s Artillery was located during the Brandywine Battle. Jacob Nagle, a young boy, son of one of General Washington’s officers, recorded events in his diary.[xiii]

The Battle of Brandywine occurred on September 11, 1777. Proctor’s Artillery arrived September 10[xiv] and hauled their cannons up the hill behind John Chad’s house. The following day, the American army was outflanked on the northern and of their line which caused Captain Courtenay to retreat, abandoning his artillery.[xv]

Ned’s heroism was recorded in his obituary.

“During the war of the revolution, his conduct on one memorable occasion, exhibited an example of patriotism and bravery which deserves to be recorded. At the battle of Brandywine he had charge of an ammunition wagon attached to Col. Proctor’s regiment, and when the American army was obliged to retreat, an order was given by the proper officers to those having charge of the wagons, to abandon them to the enemy, and save themselves by flight. The heroic reply of the deceased uttered in the true spirit of the Revolution: “The enemy shall not have my team; I will save my horses and myself!” He instantly started on his way, and as he proceeded, amid the confusion of the surrounding scene, he calmly gathered up a few stands of arms which had been left on the field by the retreating soldiers, and safely retired with his wagon, team and all, in the face of the victorious foe.”[xvi]

This is an interesting contrast to his Captain who was court-martialed and almost cashiered for leaving the field of battle in an un-officer-like manner and for losing his cannons to the enemy.[xvii]

Ned petitioned the Pennsylvania Congress in 1827[xviii], 1829[xix], and 1833[xx] for a pension. Report #218, in 1827 contained his claim for the Battle of Germantown. There is a painting of Proctor’s Artillery firing four artillery pieces at the Chew House in Philadelphia.[xxi] This painting, although done much later, give a perspective of the battle that Ned might have experienced as a bombardier. At this same location there is another painting of the battle with a black teamster hauling a wagonload of Redcoats in front of the Chew House.[xxii]

After this battle, the only reference to Ned is a on vague list telling “Negro Hector” to “express” an item in 1778.[xxiii] Here the term “express” might be used in terms of delivering mail or a package. A curious fact was that on May 19, 1778, Lafayette escaped the British forces by crossing Matson’s Ford. He retreated up what is now called Fayette Street in Conshohocken and marched past Ned’s house.[xxiv] At that time, the area was Plymouth Township; it was not incorporated as Conshohocken until 1850.[xxv]

Ned can be found on 19th-century Plymouth Township Tax Rolls from 1810 to 1825.[xxvi] He is on the 1800 Federal Census as “Negro Edward” living with five “free color persons” in his household.[xxvii] He is also listed in 1810, 1820 and 1830[xxviii], along with his wife, Jude[xxix] and children: Charles, Aaron, Isaac, and Sarah.[xxx]

There are a few additional 19th-century references to Ned and/or his family. There is a court document in 1804 stating that Ned had been robbed by a James Brown who took a scythe and “hangings.”[xxxi] The latter being the handle of the scythe blade according to Webster’s 1913 dictionary.[xxxii] His children were on the “Poor Children to be Educated at the County Expense” list, Montgomery County, for 1811, 1813 and 1815.[xxxiii] In 1790, the Pennsylvania Constitution hadprovided that children of poor families were taught free of charge.[xxxiv]

As mentioned earlier, Ned petitioned for a pension. His first was turned down on the grounds that he could not prove his length of service. The second two were also turned down. In 1833, the Pennsylvania Congress passed a law allowing anyone with as little as two months of military service to receive a $40 gratuity.[xxxv] A gratuity differs from a pension in that the latter is paid periodically and it could vary from $80 to $120. A gratuity was a one-time payment and is the only payment we know Ned received.

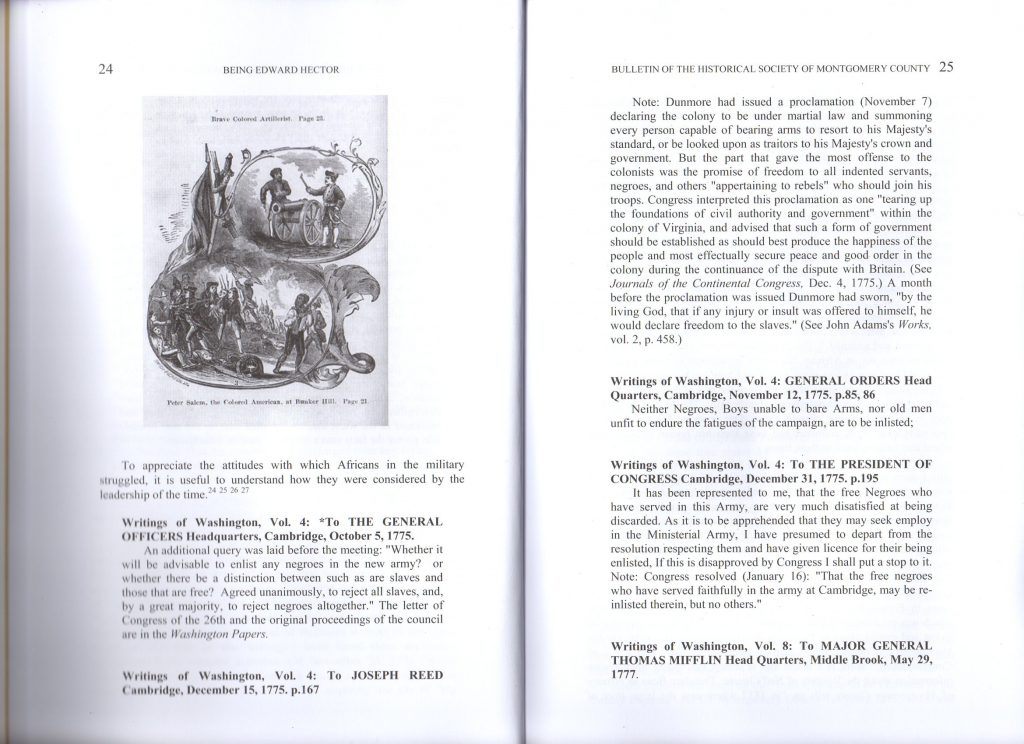

To appreciate the attitudes that Africans in the military struggled with, we must look at how they were considered by the leadership if the time. Copies of letters and orders to and from General Washington.

[5 Oct. 1775, “To the General Officers Headquarters, Cambridge] Agreed unanimously, to reject all slaves, and, by a great majority, to reject negroes altogether.[xxxvi]

[12 Nov. 1775, “General Orders Head Quarters, Cambridge] Neither Negros, Boys unable to bare [sic] Arms, nor old men unfit to endure the fatigues of the campaign, are to be inlisted.[xxxvii]

31 Dec. 1775, “To the President of Congress, Cambridge] It has been represented to me, that the free Negroes who have served in this Army, are very much disatisfied at being discarded. As it is to be apprehended that they may seek employ in the Ministerial Army, I have given license for their being enlisted. If this is disapproved by Congress I shall put a stop to it. [Note: Congress resolved (January 16) “That the free negroes who have served faithfully in the army at Cambridge, may be re-inlisted therein, but no others.”][xxxviii]

[29 May 1777, “To Major General Thomas Mifflin Head Quarters, Middle Brook] Colo. Meade informs me, that you find it difficult to procure Teamster for Horses that draw in a line, and that therefore you wish for liberty to alter the Waggons already built and make those on hand go double. To this I have no objection, if the Service will be expedited by it.[xxxix]

[22 July 1777, To Major General Israel Putnam, Head Quarters, Galloways in Smiths Clove] The necessity of drafting so many Soldiers from the Army to make Waggoners of them is a very disagreeable circumstance. But if the Quarter Masters cannot procure them, there is no way of avoiding it. And as it respects the Artillery, it will never answer to convert Artillermen, who are so much wanted with their pieces, into waggoners. Unless therefore your Quarter Master General can furnish persons for the purpose you mention, it will be necessary for you to draft a sufficient number of Soldiers, qualified for the business of Waggoners, to be attached to the Artillery.[xl]

The comments from the committee on claims where Ned’s petition was reviewed make interesting reading.

That the petitioner states that he was employed in driving: an artillery wagon, attached to the regiment commanded by col. (check quote to see if this is lower case) Proctor. That he was present at the battles of Brandywine and Germantown, and that he never received any compensation for his services. He therefore prays the Legislature to take his case into consideration, and grant him such relief as they may think proper. Your committee begs leave to remark, that there is no evidence before them, that any thing is due to the petitioner; neither is there any testimony, except his own statement and deposition, how long he did serve, or what kind of service he rendered. There is the deposition of Thomas R. Brooks, stating that he was well acquainted with the petitioner, and knows that he was in the army; but does not say what length of time, nor in what capacity, he served. Your committee would further remark, that if the statements of the petitioner were fully substantiated, they would not consider him entitled to a pension, agreeably to the practice of the Legislature hitherto. They therefore offer the following resolution:

Resolved, That the committed be discharged from any further consideration of the subject.[xli]

The community thought differently. “In 1853, three years after the borough’s incorporation, when John Wood was burgess, (mayor), and president of the new town council approved [sic] a measure to rename Barren Hill road from Fayette Street to North Lane in honor of Ned Hector, 19 years after his death. The measure approved, and . . . the road is still known as Hector Street.”[xlii] Naming a street after Ned is evidence of how highly respected he was by those in his community. To strengthen this point, the streets bearing personal names are named after prominent men of the community, except Hector Street. Think how many things are named after a black person in the mid-1800s and an appreciation of this honor can be understood.

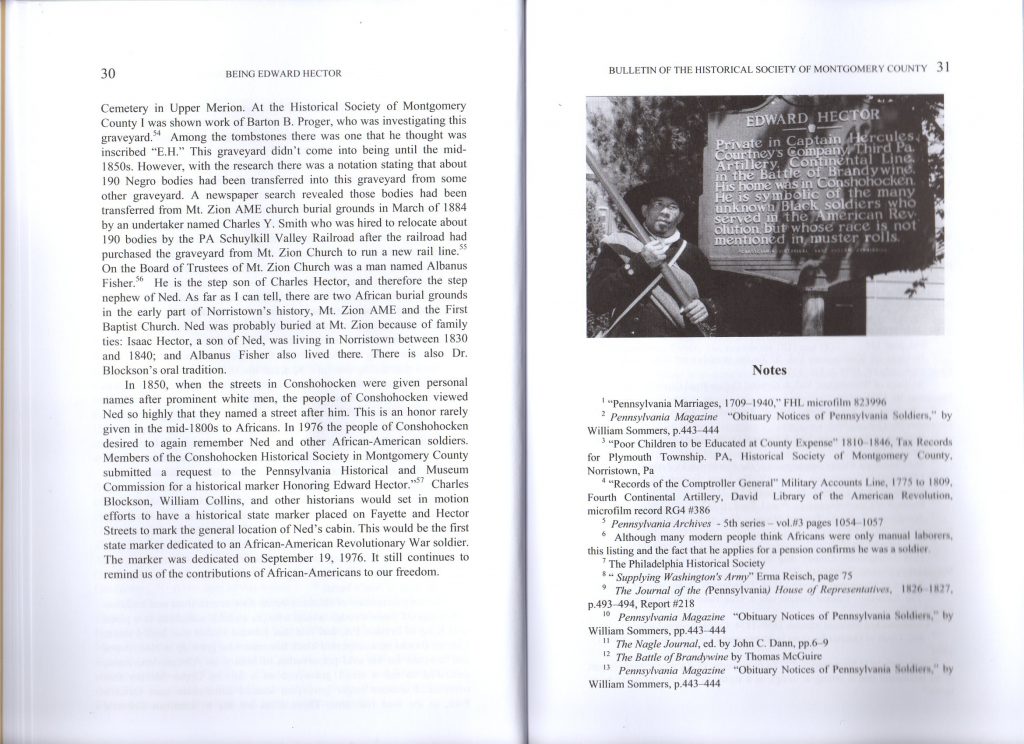

In “1976 members of the Conshohocken Society in Montgomery County submitted a request to the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission for a historical marker Honoring Edward Hector.”[xliii] Charles Blockson, William Collin, and other historians set in motion efforts to have a historical state marker placed on Fayette and Hector Streets to mark the general location of Ned’s cabin.[xliv] This would be the first state marker dedicated to honoring an African-American Revolutionary War soldier. The marker was dedicated on September 17, 1976.[xlv] It still continues to remind its readers of the contributions of African-Americans to their freedom. Their desire is what we all desire for ourselves – not to be forgotten.

[i] Julie Winch, A Gentleman of Color, ( New York, Oxford University Press, 2002 )

[ii] Richard S. Newman, Freedom’s Prophet, ( New York and London, New York University Press, 2008)

[iii] 1787 Constitution, Article IV: The States, Section 2, Clause 3

[iv] William Sommers,Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Obituary Notices of Pennsylvania Soldiers , Volume 38, p.443-444

[v] John C. Fitzpatrick, The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources 1745-1799, (U. S. Government Printing Office. Washington, DC: 1944), Vol. 4: Orders and Instructions to John Parke, Headquarters, Cambridge, April 3, 1776. p.466

[vi] Marriage Records, Christ Church, Philadelphia, Pa

[vii] Derived by subtracting 1777 [Battle of Brandywine] from 1744 [year of Edward Hector’s birth]

[viii] Thomas Lynch Montgomery, Pennsylvania Archives : Fifth Series, (Harrisburg, PA : Harrisburg Pub. Co., State Printer), vol.#3 page 1054-1057

[ix] Thomas Lynch Montgomery, Pennsylvania Archives : Fifth Series, (Harrisburg, PA : Harrisburg Pub. Co., State Printer) vol.#3 page 1054-1057

[x] General Assembly. House, Journal of the House of Representatives of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, (Pennsylvania), 1826-1827, p.493-494, Report #218

[xi] Adrian Caruana,THE LIGHT 6- POUNDER BATTALION GUN OF 1776: Historical Arms Series No. 16, (Canada, Museum Restoration, 1993)

[xii] General Assembly. House, Journal of the House of Representatives of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, (Pennsylvania), 1826-1827, p.493-494, Report #218

[xiii] John C. Dann, The Nagle Journal: A Diary of the Life of Jacob Nagle, Sailor, from the Year 1775 to 1841, (New York. Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 1988), p.6-9

[xiv] John C. Dann, The Nagle Journal: A Diary of the Life of Jacob Nagle, Sailor, from the Year 1775 to 1841, (New York. Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 1988), p.6

[xv] McGuire, Thomas J., The Philadelphia Campaign: Volume 1: Brandywine and the Fall of Philadelphia, (Stackpole Books; Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania; 2006)

[xvi] William Sommers,Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, “Obituary Notices of Pennsylvania Soldiers” , Volume 38, p.443-444

[xvii] John C. Fitzpatrick, The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources 1745-1799, (U. S. Government Printing Office. Washington, DC. 1944), Vol. 10: General Orders, Headquarters at the V. Forge, January 3, 1778. p258

[xviii] General Assembly. House, “Journal of the House of Representatives of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania”, (Pennsylvania), 1826-27 Session, Vol.1, page 853

[xix] “General Assembly. House, “Journal of the House of Representatives of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania”, (Pennsylvania), 1828-29 Session, Vol.1, page 833

[xx] General Assembly. House, “Journal of the House of Representatives of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania”, (Pennsylvania), 1832-33 Session, Vol.1, page 135

[xxi] Painting of 4 cannons belonging to Proctor’s Artillery bombarding the Chew house during the Germantown Battle located at the Chew house.

[xxii] Painting of Battle of Germantown with black teamster hauling Redcoats. Artist’s rendition of the Battle of Germantown (October 1777). (Oil, date unknown, by Xavier D. Gratta, Valley Forge (Pa.) Historical Society.)

[xxiii] “Negro Hector” in 1778 to “express” an item. NARA M247 Quartermaster Dept. 1778-80,

[xxiv] Theodore Bean, Theodore Bean’s History of Montgomery County, (PHILADELPHIA, EVERTS & PECK, 1884), Chapter XLI, Borough of Conshohocken, page 717

[xxv] Theodore Bean, Theodore Bean’s History of Montgomery County, (PHILADELPHIA, EVERTS & PECK, 1884),Chapter XLI, page 713

[xxvi] Montgomery County Tax records for 1831 and 1833

[xxvii] Federal Census records for Plymouth Township, Montgomery County, Pa, 1800

[xxviii] Federal Census records for Plymouth Township, Montgomery County Pa,1810, 1820, and 1830

[xxix] Theodore Bean, Theodore Bean’s History of Montgomery County, (PHILADELPHIA, EVERTS & PECK, 1884), Chapter XLI. Borough of Conshohocken, page 717

[xxx] Montgomery County Historical Society, “Poor Children to be Educated at County Expense” 1810-1846, Tax Records for Plymouth Township. PA., Norristown, PA

[xxxi] “Court of Quarter Sessions in Montgomery Co.” Montgomery County Historical Society, Norristown, Pa, Nov. Session, Nov. 13, 1804

[xxxii] Webster’s Dictionary, (1913 Edition), See “Hang” – definition #3

[xxxiii] Montgomery County Historical Society, “Poor Children to be Educated at County Expense” 1810-1846, Tax Records for Plymouth Township. PA., Norristown, PA

[xxxiv] Barton B. Proger, “Overview to the Pennsylvania Poor Laws and Their Impact On Education”, Montgomery County Historical Society

[xxxv] “Auditor General Revolutionary War Pension Accounts”, Pa State Archive, RG2, vol.12, page76

[xxxvi] John C. Fitzpatrick, The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources 1745-1799, (U. S. Government Printing Office. Washington, DC. 1944), Vol. 4: *To The General Officers, Headquarters, Cambridge, October 5, 1775

[xxxvii] John C. Fitzpatrick, The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources 1745-1799, (U. S. Government Printing Office. Washington, DC. 1944), Vol. 4: General Orders, Headquarters, Cambridge, November 12, 1775. p.85, 86

[xxxviii] John C. Fitzpatrick, The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources 1745-1799, (U. S. Government Printing Office. Washington, DC. 1944), Vol. 4: To The President Of Congress, Cambridge, December 31, 1775. p.195

[xxxix] John C. Fitzpatrick, The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources 1745-1799, (U. S. Government Printing Office. Washington, DC. 1944), Vol. 8: To Major General Thomas Mifflin, Headquarters, Middle Brook, May 29, 1777

[xl] John C. Fitzpatrick, The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources 1745-1799, (U. S. Government Printing Office. Washington, DC. 1944), Vol. 8: To Major General Israel Putnam, Headquarters, Galloways in Smiths Clove, July 22, 1777

[xli] General Assembly. House, “Journal of the House of Representatives of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania”, 1826-1827, (Pennsylvania), p.493-494, Report #218

[xlii] The Recorder “Edward Hector was a True Hero in Revolutionary War”, Newspaper, Montgomery County Historical Society, Norristown, Pa, Feb.17, 1994

[xliii] Charles L. Blockson, “A Brief History of the Pennsylvania Black History Committee”, Montgomery County Historical Society, Norristown, Pa

[xliv] Charles L. Blockson, “A Brief History of the Pennsylvania Black History Committee”, Montgomery County Historical Society, Norristown, Pa

[xlv] Charles L. Blockson, “A Brief History of the Pennsylvania Black History Committee”, Montgomery County Historical Society, Norristown, Pa

Ned Hector’s experiences have been described in a history book for children: Noah Lewis and Loretta Graham, Edward “Ned” Hector: Revolutionary War Hero – Time Traveler (Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse, 2005)

Bulletin of the Historical Society of Montgomery County Pennsylvania

Being Edward Hector –

The Life and Times of a Black Revolutionary War Hero

By Noah Lewis

Vol. 36, Number 4, 2013, pages 19 – 33